Saving Spaghetti

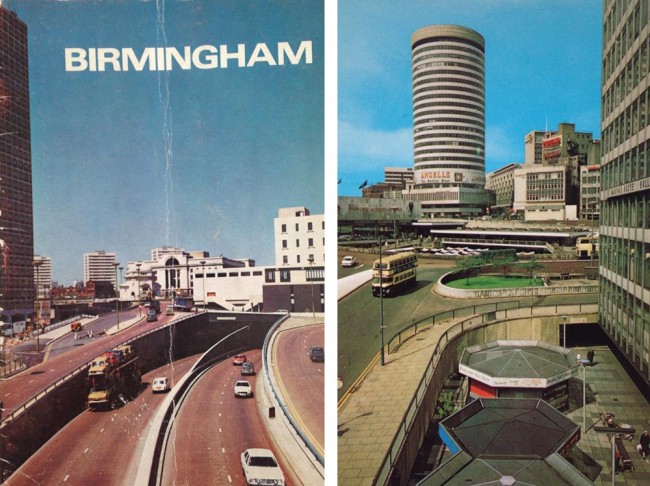

The inner ring road and the infrastructure of the Manzoni era (1930’s to 1960’s) is today widely held as the biggest error in post war planning in Birmingham, itself often held up as an example of the failure of modern planning in Britain. The ‘concrete ring’ strangles the city core, separating it from its surrounding quarters, discouraging explorers with its roaring underpasses and public gardens beneath Lancaster Circus and Five Ways. The current masterplan or ‘Big City Plan’ in my opinion rightly seeks to neutralize the inner ring’s effect, but in doing so presents a subtle problem in conservation terms.

There are many obviously fine buildings ‘at risk’ throughout Birmingham, subjects of the recent Re-Imagine competition like Moseley Road Baths or the Golden Lion Inn. The problem is that they are not at present self-sustaining economically, and until the tide of economic growth rises somewhat higher, will probably not receive subsidy to be able to be restored or used in a way that fits their original purposes, as would be the goal of ‘pure conservation’. So sadly, even our city’s best and most loved historic buildings are at risk. What then for our lesser and unloved relics?

English Heritage’s book English Heritage’s book Images of Change: England’s Late 20th Century Landscapes by Sefryn Penrose discussed and proposed retaining (slightly warily) the structures and places that are representative of the 20th century. Not the obvious show-piece buildings like the Barbican or Southbank Centre, but the Butlins’, the prisons, the powerstations (Battersea, Tate Modern’s Bankside) that really represented Britain as it was, rather than how it wanted to be. Forgetting cost, if we were to apply the same thinking to Birmingham, what would be keep?

The infrastructure of the 1950’s onwards is representative of a ‘chapter’ in the city’s history. It has, or will have historic value in time, but should it, or can it, be preserved in any meaningful way? Perhaps it is a ‘mistake’, and should be forgotten, although we do not try to forget wars or other tragic events. Or perhaps it should be preserved in the belief that all things, eventually, become beautiful, nostalgic or romantic?

The – I believe apocryphal – “More canals than Venice” strap-line of Birmingham’s 90’s regeneration is occasionally still heard, and it seems remarkable that there was a time when canals were considered unpleasant urban detritus. Black, shopping-trolley infested fault lines through the city where only the brave ventured. But early adopters found romance there, like Richard Mabey in ‘The Unofficial Countryside’. Now they are ‘green lungs’, sites of gentrification, paths for joggers, cyclists and anglers, a rich resource. Will we ever see the underpasses, round-about-gardens, flyovers and tunnels as similarly attractive?

No one is proposing the whole-sale demolition of the ring road, but it and all its elements will be gradually eroded, and an evocative period of the city’s history will disappear. But, the thought of earnest black clad design buffs mounting protests at the loss of a ceramic clad underpass which is ‘delightfully evocative of the motor age’ is quite unpleasant. So what, if anything, might we keep from this period, if we could afford it, or can continue to find a use for?

Spaghetti Junction perhaps, the great, self-defeatingly labelled Brummie landmark. I travelled over it many times as child travelling with my family from Leicester, and it was to me legendary for its apparent complexity, and the unlovely views over the concrete barriers of the M6. Moving to Birmingham in my late twenties, I was amazed to discover it was basically a cross roads between the M6 and A38, and I still have no idea why they made such a meal of it.

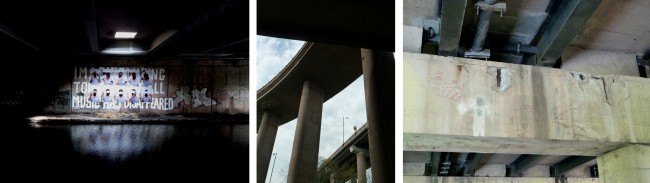

But I was literally awe-struck the first time I walked under it, following the canal from Aston Junction to walk around the Heartlands Loop. I was reading at the time Paul Farley & Michael Symmons Roberts’ wonderful Edgelands, along with Richard Mabey, and Iain Sinclair, all writers who taught me to look at the every-day in the city with fresh eyes.

“…underneath this long, extended bridge, this complex of flyovers, is another world… dark, damp, intense and menacing. Peel off the flyover and circle round to get to the edgelands below… we see the River Tame, a Styx in semi-darkness mirroring the journey of the flyover above… It is as if we can see inside the body of a road, its viscera, its bloodstream” (p.131 to 132).

Okay, you’re not convinced.

Well anyway, while travelling both below and over it is something of a niche interest, it can’t be denied that Spaghetti Junction is a masterpiece of engineering. My brain aches at the thought of designing concrete bridges, curving in three dimensions without a computer. My brain aches at the thought of designing them with a computer. A marvellous relic of post-war British ingenuity and know-how, and a symbol of space-age optimism.

It is gradually decaying, as all things do, and is being steadily repaired. Will there come a time where we decide to conserve it? English Heritage recently published their 360 odd page manual on conservation of historic concrete (enlightening, although not a rollercoaster of a read). I very much doubt the engineers repairing Spaghetti Junction have referred to it, and who now would expect them to?

Perhaps buildings (etcetera) should be conserved in the manner that they were built – if rationally utilitarian, then be ready to be torn down and replaced when the need arises. We can’t keep everything from history, like tragic hoarders who are found in their flats surrounded by bales of newspapers. And this is especially so where historic artefacts occupy valuable real estate within a city, causing inconvenience or demanding precious public funding.

We must have strange ideas of Georgian England from the sprinkling of artefacts that have remained, valuable enough to be reused. What then will we keep from this period of Birmingham’s history to remember the mistakes, or indeed, smile at an optimistic time? And what strange ideas will future generations have of it?

Thanks to Andrew Kulman, English Heritage, Suburban Birmingham (all as credited).

For a wonderful archive of Birmingham before and after the ring road, see the P J Norton collection.

Steve, thanks for the great links – the Highline particularly is a brilliant example of how redundant infrastructure can be made into a real asset for a city. It’s a “why didn’t I think of that” project, so obvious when someone else thinks of it! Could the same thinking be applied to underpasses and so on that are at the moment being filled in because they’re too unsafe? Just as buildings can be thoughtfully adapted to maintain their historical value while generating income, so could infrastructure. I’m thinking of the flyover next to the mailbox, just some simple lighting really ‘lifts’ it, and the Flyover Festival at Hockley is another example of where these spaces can be made use of. How can we maintain this period of the city’s history, while creating exciting and valuable assets for today and the future?

Thanks Matt. l was at The street Arts festival yesterday and passed under lots of bridges. The area around The Mailbox has a lot of potential it reminds me of parts of the South bank in London. I searched for Flyover Festival looks like a few are popping up- pretty cool.

As for the safety issue, were the underpasses filled in due to fear of crime or structural reasons? I don’t know the price of concrete per tonne and the other associated costs but I’d have thought it was cheaper to put up a few lights, a lick of paint and some plants. It must be better to this than pouring more concrete. http://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whatson/festivals-series/festival-of-neighbourhood/queen-elizabeth-hall-roof-garden-and-woodland-garden-fon-explore It encourages bio diversity and social benefits. I met one of the volunteers who told me it had changed his life!

Creating incentives to make working with existing structures may be the way to maintain present and future assets as they have embodied energy in them-even the ugly ones!. A new attitude to conservation and tax breaks that make it cheaper to conserve/reuse would be a good start. As a businesses bottom line will be their bigger priority.

An interesting article. I don’t know a huge amount about it but having been on it when I was younger it did seem over engineered and confusing. I think possibly if taking part of it down to rectify this is the best solution then so be it. I read there were plans to light it up as art installation so that it could be seen from space to turn it into a real feature. Aside from light pollution planners need to look at the bigger picture in terms of social and community benefit. It seems at times these ‘suits’ are more interested in furthering their careers by being associated with a big idea than delivery of services that are needed and have long term impact. I think we can enhance existing structures by re-greening with vertical gardens, parks. Markets, pop -up festivals and good quality temporary structures for business or accommodation that are adaptive to changing circumstances. These type of options as a model reconnect the city. This is nothing too out-of-the-box, just re-thinking what works and applying them in different contexts.

http://designtrust.org/projects/under-elevated/activities-and-outputs/

http://designtrust.org/projects/reclaiming-high-line/

Basic examples.

Thought provoking article. Very pleased to see the website alive with debate of this nature.

Thanks for your comments! I agree Suzanne, buildings seem to go through a phase of being loved when new, then become an embarrassment, before finally becoming loved again. They just have to survive the phase where they’re out of fashion. Or are some buildings beautiful no matter their style or fashion? Thanks for your comments too Leila, I like your comparison between a person and a place’s history being made of both ‘good’ and ‘bad’ events / things. I guess sometimes ‘bad’ events in a person’s life are called ‘character building’ and are actually a good thing? I think the best cities are ones that have for hundreds of years built the best they can and treasured each generation of buildings, not throwing out the old, but also not being scared of the new.

What a good article. I agree, we cannot keep everything from the past and the priority has to be a city that is a pleasure to live and work in today. But I also feel strongly that a large part of what makes a city a pleasure to be in, increases its residents’ pride, creates a buzz nationally and internationally and thus attracts investment – is a strong sense of identity and pride. Spaghetti Junction, like the Rotunda or the markets or the canals, is a very important part our past, our history; our identity. The new buildings are good to have, but they can’t create an image of a city ( a dream city) without some of the old buildings and structures to give them context – importantly, even the mistakes. A person’s whole identity is composed of their memories, both good and bad, and the same with a city – you have to accept and adapt the past, rather than just tear it down as if you were ashamed of it. I don’t know whether we should keep SJ or not, and if so in what form/ to what extent. There must be something exciting and useful that could be done with the structure when it becomes obsolete (sky orchards/ parks?) but I expect it will cost a lot of money that isn’t there, etc. But taking that approach, making something good out of an old mistake, would be the best thing for Birmingham in the long run.

Very interesting read Matt. I find fascinating that at one time everyone was going crazy for building in concrete in the same way that today gold metal cladding is appearing on so many new builds. Yesterday’s fashions seem to be today’s mistakes! Personally, I LOVE spaghetti junction – especially now as my sons shout from the back of the car when we drive on it – “go pasta, pasta mummy”! Good read Matt. Made me think.